Brainrot Rhetoric

And the choice before us

One of the best essays I’ve ever read on Substack is Sam Kriss’s “In my zombie era,” which discusses brainrot culture through a zombie’s brainrot narrative. For example:

Every day I spawn in. Emerge wriggling out my skibidi bolus of slime. Whence and where? Lol. Idk. Vibes here be mad shady fr…Here’s a normal day in the life of a mf with zero inner monologue and zero ability to speak. From 6 to 7 am I bedrot, or I would if I had a bed. Instead I simply rot. Goblincore. Mushroomcore. Livid colonies of fungus going feral around my wounds fr. From 7 to 8 am I bedrot. From 8 to 9 am I bedrot. From 9 to 10 am I flail my arms around while making strangled hacking noises. No cap this is such a dope part of my morning routine. From 10 am until lunch I enter grind mode, by which I mean wandering in loose circles over the ruins.

After this goes on for awhile, Kriss moves to third person to offer analysis:

If the hipster represents cultural taste as sorting algorithm, and the nerd represents cultural taste determined by sorting algorithm, the zombie is the point at which we stop consuming culture-commodities altogether and start directly consuming the sorting algorithm itself.

In an age of overwhelming content, the hipster initially helped sort through it all by being a tastemaker themselves. Then that role was handed over to programmers who created algorithms that would sort and deliver to you the best cultural tidbits. Now, people are consuming the algorithms directly.

He gives the example of the stereotypical TikTok doomscroller. If you watch someone in the throes of it, they aren’t actually watching the videos. They are instead glancing at and then flicking through the vast majority of them. It’s not that their parents were watching 2-hour films, and they now watch 30 second clips. The scrolling is now the point of it. The algorithm is the entertainment.

Kriss believes Twitch, the popular streaming platform, is the fullest expression of this phenomenon. Streams go for hours, sometimes including while the streamer is sleeping, and rarely rise above commentary like, “This dual hammer meta is absolutely disgusting and I really hope they patch them immediately and make them share global cooldown.”

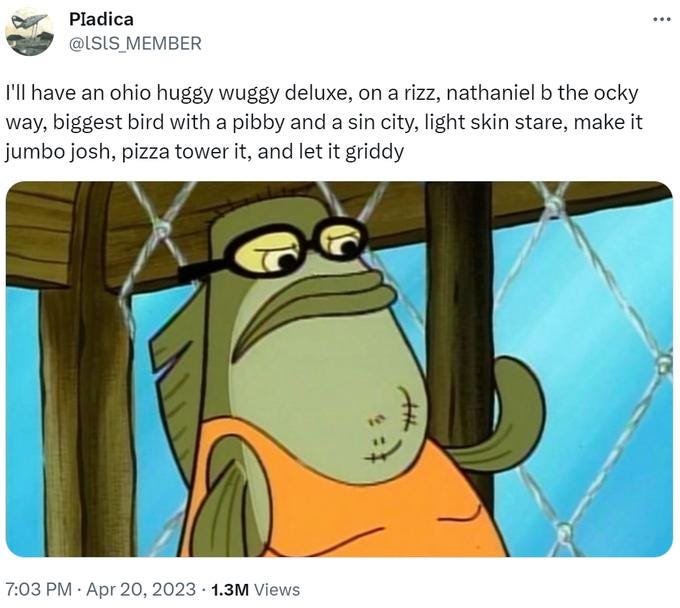

Nevertheless, Twitch is the platform of the future and the incubator for the next generation of micro-celebrities (and slang). The dialect is less about referencing a specific cultural artifact — e.g. “Assistant to the Regional Manager” — and more about glorying in your familiarity with the platform’s jargon. In other words, buckle up for a lot more of this:

“Many parents and teachers have become irritated to the point of distraction at the way the weed-style growth of “like” has spread through the idiom of the young…the term has become simultaneously a crutch and a tic, driving out the rest of the vocabulary as candy expels vegetables” - Christopher Hitchens

Valerie Fridland argues in her 2023 book Like, Literally, Dude that people who claim spoken English is deteriorating are hypocritical curmudgeons. They are hypocritical because language always changes. You don’t speak the English of Beowulf, do you?

More than that, she believes “there is no right way to speak English” is a moral stance. Holding up any norms would allow the continued marginalization of immigrants, women, minorities, etc.

As an etymological history, her book is full of interesting notes. For instance, while um and uh can seem like dead space, she argues they have all sorts of valuable uses. If you want to hold the floor while you remember what you wanted to say, you can just toss out an ummmm (which generally implies more cognitive processing required than a mere uh).

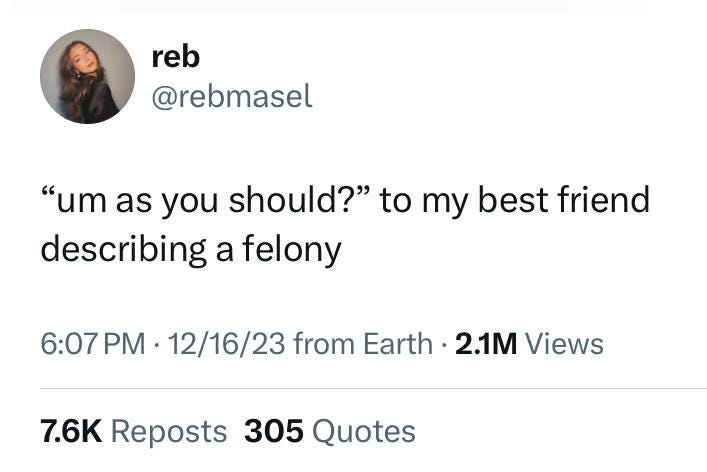

What’s more, young women, who tend to be linguistic innovators — they started using going to instead of will, have to instead of must, and really instead of very — have now turned um into a sarcastic sentence opener:

As a linguistic polemic, I find Fridland’s book less convincing. It’s one thing to say that Southern accents shouldn’t be stigmatized. I also acknowledge that saying, “It took, like, twenty minutes,” or “I was like…,” or “And when I heard that, like, my heart dropped” all have a different effect than saying, “It took twenty minutes,” or “I told him…” or “And when I heard that my heart dropped.” Like is a versatile, playful word whose enduring popularity — despite attacks from Christopher Hitchens and others — signals a certain value to its users.

Nevertheless, Fridland wrongly elides differences in usage (a Southern accent versus a Northern one) with differences in effort (littering your speech with like, um, and profanity).

In her disdain for linguistic prescriptivists, she becomes a sort of linguistic populist, appealing to the natural instinct of ordinary speakers over any kind of historic norm. Quite literally, vox populi, vox dei. And while that seems compassionate and righteous at first glance, linguistic populism carries the same risks as political populism. It is easier to tear down than build up.

“Important art forms will survive only because of a frank elitism, an insistence on distinction, a contempt for mediocrity.” - Ross Douthat

The internet is a vulgar place.

Of course, there’s the violence, the sexuality, and the obscenity, but at root, vulgarity means something like philistinism — a lack of sophistication. It comes from the Latin vulgus meaning “common people.” Vulgarity in its fullest sense is something that is both popular and in poor taste. (Sometimes, things are “in poor taste” merely because they are popular).

That’s why Henry Higgins, the phonetics professor in Pygmalion and My Fair Lady, is not merely concerned with changing Eliza Doolittle’s vowel sounds. Higgins admits that most upper class ladies are dreadfully boring and Eliza could fit in with a little vocal work so long as she stuck to pleasantries.

But to become a lady, truly, is another matter. As Higgins tells her, “Oh, it’s a fine life, the life of the gutter. It’s real: it’s warm: it’s violent: you can feel it through the thickest skin: you can taste it and smell it without any training or any work. Not like Science and Literature and Classical Music and Philosophy and Art.”

To Higgins, the work of rhetoric, of speaking well and clearly, is not incidental to the refinement of a proper lady. Instead, he sees discipline of speech as connected to the discipline it takes to appreciate art, literature, and music. While Fridland argues that the enduring popularity of like signals its utility and rightful place in our language, Higgins might argue that its ease and thoughtlessness disqualify it from the vocabulary of a gentlemen or lady.

It is as vulgar a word as any of the other four-letter ones.

Of course, that sentiment, just like the Douthat quote above, comes off as rather harsh. It sounds retrograde and condescending. And any norm necessarily carries the risk of being weaponized.

But the historic understanding of rhetoric and the liberal arts was that it benefitted the student first and foremost. That to become a fully formed person and citizen, you needed to train yourself. The great books were not a way to exclude but a way to elevate.

If virtue is the midpoint between two vices, you always need to consider which vice you are closer to. For most modern people, our speech is too bloated and profane rather than too spare and stiff. Our leisure time is too passive and self-indulgent rather than too rigorous and edifying. Our greater danger is not that we would become robots but that we would become beasts.

“We must labor to be beautiful” - W.B. Yeats

A few years ago, Martin Scorsese expressed the controversial opinion that Marvel movies aren’t cinema, they are more like an amusement park ride. 5 years later, Netflix is explicitly telling filmmakers to “have this character announce what they’re doing so that viewers who have this program on in the background can follow along.”

Podcasts were once praised as a new opportunity for in-depth conversations, a chance to go deeper than a 5 minute radio spot. They have become a new form of talk radio offering hours of entertaining background noise.

Social media gave people a chance to exercise their creativity, and an iPhone put a production studio in your pocket. This has culminated in Twitch, a streaming platform that excels at running in the background.

All these different forms have converged on slop.

There are plenty of reasons for this. Platforms moving toward ad-supported content have incentives to maximize total engagement rather than the quality of that engagement. Cultural aspiration is now viewed with scorn. Awards shows praise irrelevant, self-congratulatory works of art.

The million dollar question is whether you can convince people that this is as good as it gets.

Ted Gioia wrote about a study that tested whether you could trick people into liking bad art. A sample of 12,000 people were given access to a private music service. Half saw the actual rankings of the most popular songs while the other half saw some songs artificially inflated in their popularity.

In other words, the test was whether you’d trust your own judgment or the system’s promotion of inferior music. Gioia explained:

There were three lessons learned from this study—and I believe that they are extremely important:

Yes, the system could manipulate people into downloading and listening to inferior songs—simply by lying about their popularity.

But this only worked in the short run. Over time, listeners would return to the better songs no matter what the fake rankings said.

The scariest part of the story is that fans who were lied to—given crappy songs and told that they were great—eventually lost interest in all the songs. They listened to less music. They cared about it less.

That last point rings true to me.

At first, Marvel trounces “cinema,” but then no one ends up going to the movies. At first, book candy replaces the classics, but then kids stop reading altogether. At first, Moral Therapeutic Deism replaces Christianity, but then that’s replaced by the Void.

So here we are at a pivot point. Some will continue barreling down the path we’re on, tearing down what little there is left.

Others will rebuild.

They will clean up their speech, they will pick up their books, and they will go back to church. They will dispense with ironic detachment. They will commit themselves to their families and communities, knowing that these offer the greatest joys in life, as well as the greatest risks. They will not bedrot. They will not brainrot.

St. Irenaeus said that “the glory of God is a human being fully alive.”

So rather than zombies, let us live life, and live it to the full.

I loved this whole post. The only improvement I could imagine would’ve been adding “One of the best ‘non-Griffin-Gooch’ essays I’ve seen on Substack” to your opener line, but perhaps this was already implied

I loved this! It’s always a pleasure when an article opens many more doors of reading and discovery— so thank you for your contribution!