The Jedi Knight Method of Evangelism

Evangelism for Brokenists

The man appeared to be wearing a Jedi robe. As he stood on a busy DC crosswalk, I couldn’t tell if he was directing traffic or doing calisthenics. He was lunging down one moment and then thrusting both arms overhead the next. I walked over to say hello.

I was a young intern at the time, and I figured our conversation might make for a good story that night. As I got closer, I saw that he was holding a large wooden cross in his hand. He was not, in fact, a street performer. He was a monk.

When I asked what he was doing there, he said something to the effect of: “God told me to raise this cross up in the sight of all, so that’s why I’m out here.” He was from a nearby monastery, and he’d come down to Pennsylvania Avenue that day so that all the commuters would see the cross lifted up as they made their way home.

Up until that point, I’m not sure I’d ever seen a monk except in movies. In that sense, an Orthodox monastic and a Jedi knight were almost equally fantastical concepts and seeing this man on my evening commute was jarring. He was so confident in the importance of his work, so fearless of the judgment of passersby, and so calm in the face of inquiry.

I was wearing a suit, walking along with the other Capitol Hill staffers. He was in a cassock, leading a Zumba class for rush hour traffic. Yet I came away thinking, “He’s got things figured out.”

Alana Newhouse has argued that the real political divide today is not between Left and Right but between Status-quoists and Brokenists. Status-quoists believe that various institutions are decaying or struggling, “but they will learn, reform, and recover, and they need our help to do so. What isn’t needed, and is in fact anathema, is any effort to inject more perceived radicalism into an already toxic and polarized American society.”

Meanwhile, Brokenists “believe that our current institutions, elites, intellectual and cultural life, and the quality of services that many of us depend on have been hollowed out.” No matter their political affiliation, Brokenists are united in a shared belief that “what used to work is not working for enough people anymore.”

For a lot of young people today, Brokenism is a gut instinct.

They see entitlements that’ll never pay out or student loans that’ll never be paid off or housing prices that’ll never come down and think, “Why not shake things up?” And that’s not all.

The sexual revolution didn’t work. Pornography is not benign. Divorce is not harmless. Social media is not community. The parents who raised their children without moral direction did not free them — they burdened them with the need to create an entire worldview from scratch. And then they wondered why their kids aren’t happy.

As for religion, Zoomers are the least likely to go to church weekly and the most likely to have never attended. Nevertheless, they are half as likely as their parents to identify as atheists. In other words, New Atheism is out; crystals, horoscopes, the occult — spirituality writ large — is back in. This encompasses everything from New Age mumbo-jumbo to Orthodox Christianity.

Sometimes commentators go too far with this and say things like, “It’s kind of punk rock to be conservative now, you know? Like, getting married young, having kids, going to church — that’s kind of cool.”

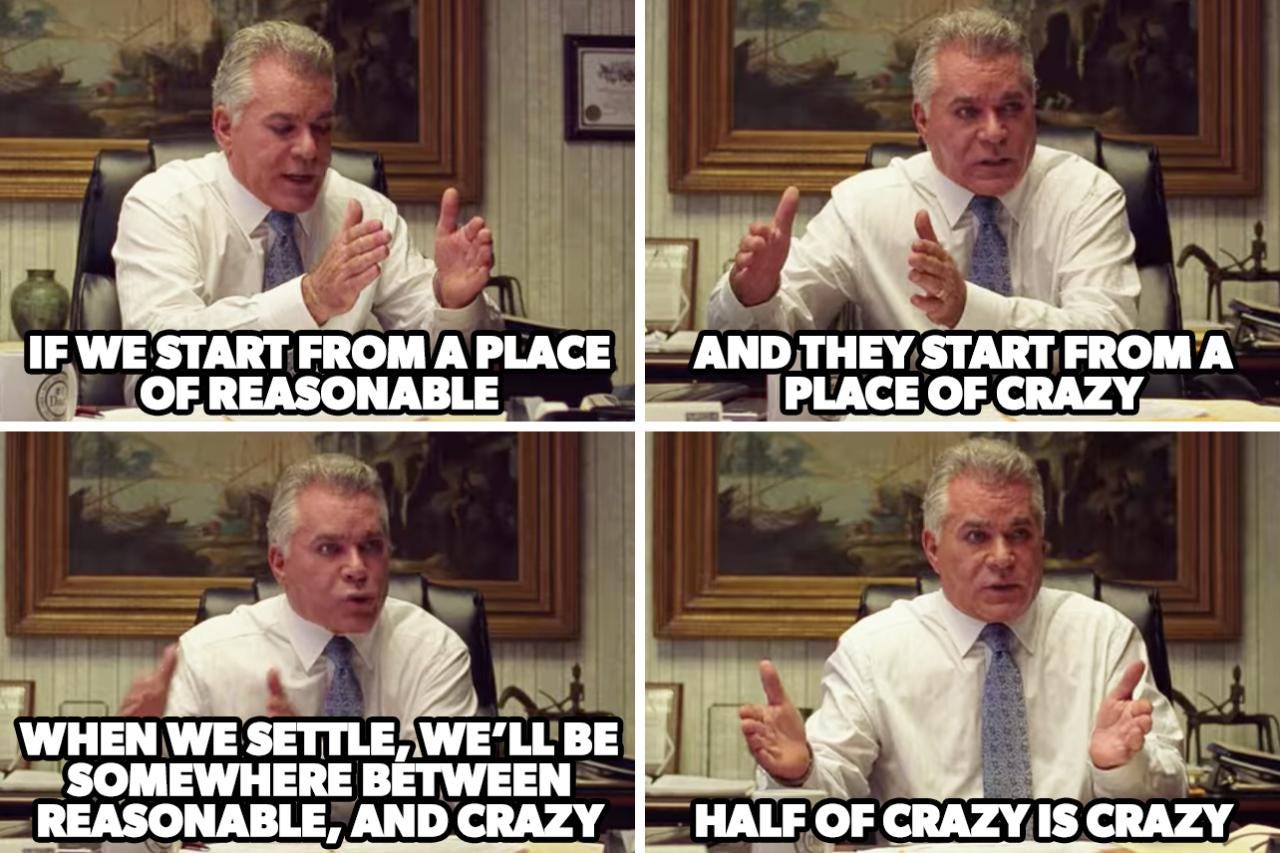

I disagree. I don’t think Ned Flanders is having a moment. It’s less about being cool than just trying to escape the crazy. The more helpful framework would be the scene from Marriage Story where Ray Liotta’s character explains divorce negotiations.

Brokenism is a belief that things are crazy. An equally crazy response can land you in all sorts of places — not all of them better than where you started. What you definitely don’t want, though, is a Christianized version of the mainstream culture, a Status-quoist Christianity.

That monk I met on Pennsylvania Ave passed the prerequisite for speaking to a Brokenist. He began from a place of crazy. At least, crazy to modern eyes. But I ended up joining the Orthodox Church years later, and now I do all sorts of things I once would’ve found strange. So, in some way, it worked.

In honor of that encounter, I’d like to expound on three rules of what I’m calling the Jedi Knight Method of Evangelism.

Rule #1: Jedi Aren’t Embarrassed

At a recent conference, Mary Harrington was discussing how in the U.K., the churches that are seeing the most growth are the Pentecostals, and the Eastern Orthodox and TradCaths. In other words, the fringes.

Here’s why:

If you just want an experience, you want to go shopping on Sunday, there's no shortage of places you can do that, but if you want to feel — if you want to feel the thing and you don't necessarily know how to put that into words, then you need a form of worship where people do the thing and aren't embarrassed about it.

And honestly that's at the high church end and it's the low church and everybody in the middle is desperately embarrassed.

The middle-of-the-road ministers remind me of English professors I had in college. While in theory they loved books, in practice they often were more concerned with technical details (the use of commas in Moby Dick) or critical readings (queer bodies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream). As an essay in The Point summarized, you end up with literature professors who basically hate literature:

Our professors had a great deal invested in novels and poems; and it was probably even the case that, at some point, they had loved them. But they had convinced themselves that to justify the “study” of literature it was necessary to immunize themselves against this love, and within the profession the highest status went to those for whom admiration and attachment had most fully morphed into their opposites. Their hatred of literature manifested itself in their embrace of theories and methods that downgraded and instrumentalized literary experience, in their moralistic condemnation of the literary works they judged ideologically unsound, and in their attempt to pass on to their students their suspicion of literature’s most powerful imaginative effects.

Likewise, I’ve met many pastors over the years who don’t seem very interested in Jesus. They’re clearly very invested in Christianity, but somewhere along the way, they found that the loving Jesus part was a liability. They’d rather talk about how Jesus was a little bit racist with that Syrophoenician woman or how Lent is really about loving yourself or how the Holy Spirit is a woman. As Daniel French recently wrote, these clergy “can speak eloquently about your carbon footprint but seem to show little interest in the inner life, let alone the salvific work of Christ.”

They have a general embarrassment, lack of confidence, or even self-loathing with respect to their office as a public Christian. And to a Brokenist, that crisis of confidence just signals another institution on its way out. No help to be found there.

Rule #2: Jedi Aren’t Performers

Before Fr. Andrew Stephen Damick became an Orthodox priest, he was a stagehand. He recalls working a few shows for Dave Matthews Band and whenever they played, “Ants Marching,” they would always shine bright lights on the crowd at the climax of the song. The audience would erupt every time.

Fr. Andrew was going to the beginnings of a megachurch at the time, and one Sunday morning he was looking around at people with hands raised, clearly having a powerful experience. And he had an admittedly cynical thought: “I can, through my professional skills, make them have this experience. Whether I believe in it or not, through the technique of the music and the lights . . . you can absolutely press a button and they’re suddenly having an experience.”

He says that disillusioned him, but he found in Orthodoxy something that operated at a deeper level than emotions, something that couldn’t be replicated by mere technique.

When you step into Liturgy, you get the sense that this really isn’t about you. That can be off-putting at first (where’s all the seeker-sensitivity?), but over time, it’s freeing. It shifts the mindset from a consumer shopping for an emotional experience (or even a culture warrior looking for fellow soldiers) to a pilgrim on the slow path to salvation. And that selects for a different type of pastor and parishioner.

I’m not saying this is some hot new church growth strategy: “the worship band is out: bring in the cantors!” But when so much of your life is tailored to you – your targeted ads, your Netflix recommendations, your algorithm – the Divine Liturgy’s gravitas pulls you out of the navel-gazing of “Do I like this” and into something bigger: “Is this true?”

Rule #3: Jedi Aren’t Compromisers

When Obi-Wan explains the Force to Luke, it’s a complete worldview. He doesn’t attempt to shoehorn it in to Luke’s preexisting framework, and throughout A New Hope, we see the tension between scientism and religion. When the upstart Admiral Motti mocks Darth Vader for his “sorcerer’s ways” and “ancient religion,” Vader uses the Force to choke him and famously concludes: “I find your lack of faith disturbing.”

In that moment, the power of the Force is an undeniable reality.

When religion is framed as a nice-to-have — you’ll feel more at peace, you’ll build community, it’ll stabilize society, etc. — this maintains the relativistic, therapeutic frame of secular culture.

When Christians accept these premises, they are reduced to arguing about how Christianity is good for sexual mores, for women and children, or for the sake of the West. Whether it’s true, whether Jesus is Lord — that’s off-limits.

So it’s quite refreshing to be around people who don’t mince words: “There is only one reality. Prayer, temptation, sin – these are all connected and don’t make sense in isolation within the secular frame. If you accept them, things will make a whole lot more sense. If you don’t, then you’ll continue to flail about. But your choice won’t change the reality of the situation.”

That’s why a project like Jonathan Pageau’s The Symbolic World or Dr. ZacPorcu’s The Roots of Everything are so important (and popular). When they challenge the separation of spirit and matter, the Western tendency to see the world as inanimate parts, or the rationalization of Evil, they are offering an alternative imaginative framework — one grounded in an older tradition. Brokenists find this compelling: materialism, rationalism, and secularism aren’t working, so maybe historic Christianity will.

Brokenists are united by their dissatisfaction with the status quo, but that’s no guarantee of success. Revolutions can (and often do) make things even worse. The greater challenge is offering a better replacement, and here I think Brokenists don’t go far enough. They’re stuck at a critique of our welfare state, hook-up culture, or consumer capitalism — that’s what’s broken, they say — but the rot goes much deeper than that.

The real brokenness in our world is sin, which means the first step isn’t tearing down our institutions, it’s tearing down all the high places in our own hearts. It’s taking responsibility for the sin we contribute to the world rather than obsessing over the sins of others. It’s repentance rather than resentment.

Unfortunately, repentance is a whole lot harder than throwing stones, so most of us stick to blaming others. But by God’s grace, the Brokenist who begins like the pharisee: “I thank you Lord that I am not like other men,” will end up saying with the publican: “Lord have mercy on me, a sinner.”

Great piece, Ben. Love the Jedi comparison. I'm reminded of "May the force be with you" every time at Mass the priest says, "The Lord be with you."