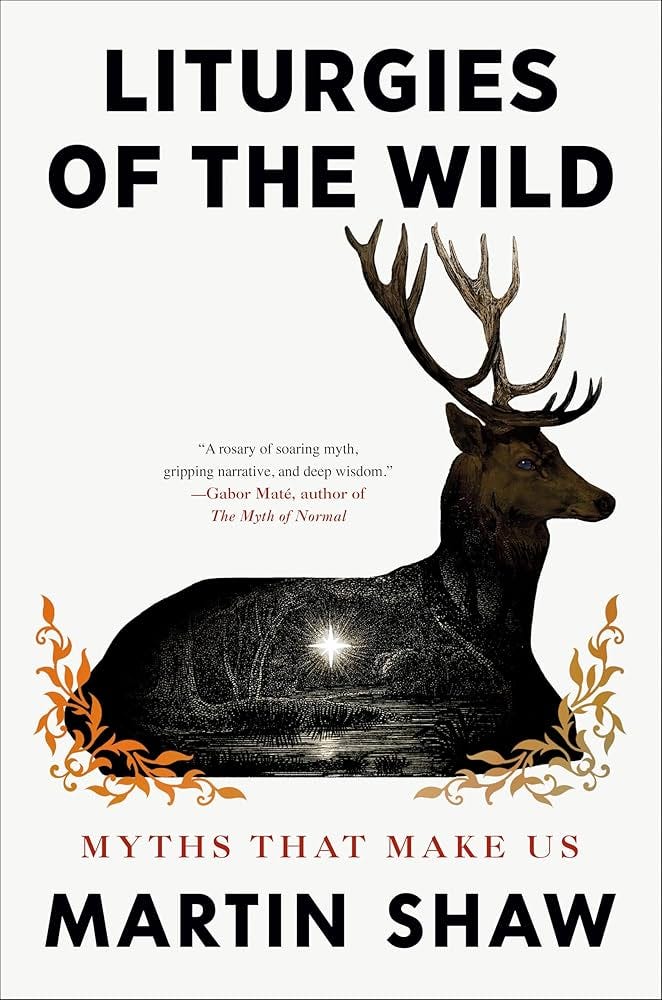

Martin Shaw Has a Story You Need to Hear

Liturgies of the Wild offers healing myths to a story-sick culture

Matt Damon’s new film The Rip recently debuted on Netflix, and he was describing how in the old days, you’d save your biggest action sequence for the climactic third act, but now Netflix execs are asking, “Can we get a big one in the first five minutes? We want people to stay tuned in. And it wouldn’t be terrible if you reiterated the plot three or four times in the dialogue because people are on their phones while they’re watching.”

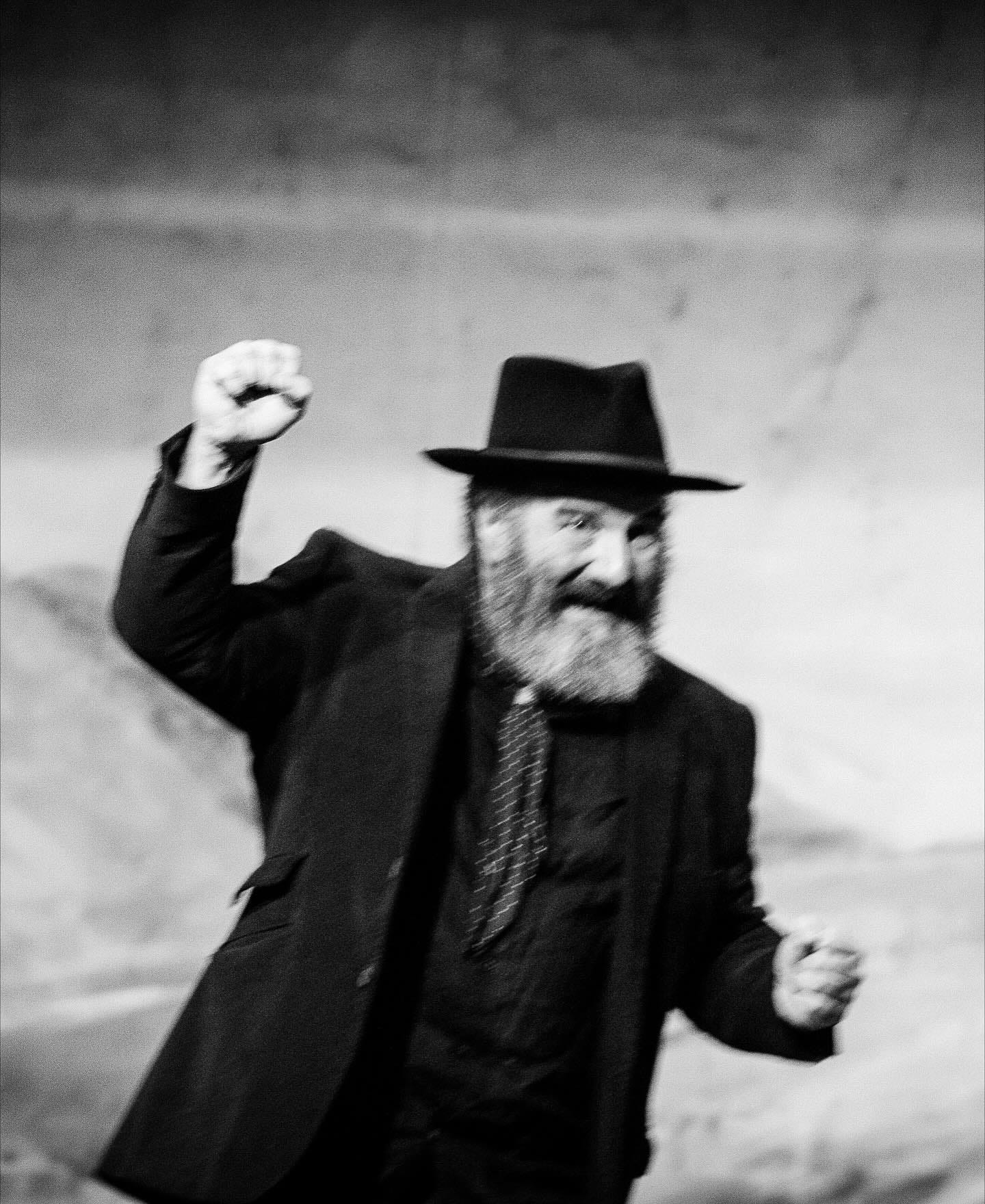

In a world where this sort of distracted, dumbed-down storytelling is increasingly the norm, Martin Shaw’s new book Liturgies of the Wild feels like a dispatch from another time—which is fitting considering Shaw himself looks like he wandered off the set of The Lord of the Rings. He lives like it too. After spending his early years as a touring musician, he spent four years living in a tent in the English hills as a sort of self-directed apprenticeship in bardic storytelling. You can imagine he’d feel quite at home dancing and singing on a table: “The only brew for the brave and true…comes from The Green Dragon!”

A few years ago, Shaw held a 101-night vigil to celebrate his 50th birthday, and on the last night, he had a vision. He saw a light with all the colors of the aurora borealis fall to earth. As it fell, it took the shape of an arrowhead aimed directly at him. Just before impact, the arrow plunged into the trees to his right. After a few seconds, it was sucked into the forest floor and disappeared. When he laid down in his bed that night, he closed his eyes and saw nine words, “Inhabit the Time and Genesis of Your Original Home.”

He admits that “it’s an odd phrase; with little skips that make it hard to pin down, it flips like a salmon in the hand and is gone.” Over the coming months and years, he would come to interpret it, at least in part, as a call to return to Eden, his ancestral home, but also to his geographic roots in England. Not too long after, after nearly 30 years away from Christianity, he was baptized into the Eastern Orthodox Church, and his recounting of that event has Shaw’s characteristic evocative diction:

I was baptised in late winter, in the depths of a Dartmoor river, by a man as much goat as priest. My father beside me, us all slip and slidy and jubilant into the dark currents. Afterwards I sat on the bank and wept like a child.

His conversion caused him some trouble. He’d spent decades building a readership as a storyteller, and now all of a sudden, he’d become a Christian—the most tired story of them all. It was all well and good when he was just telling stories about beautiful things, but the gospels “have a zip code,” as he puts it. They really occurred in time and space, and they demand a verdict.

At the same time, while that sort of confessional belief may have alienated some readers, for others, it’s a welcome change. If you’re weary of all this mythological talk after watching Jordan Peterson debate Richard Dawkins on the reality of dragons and Nellie Bowles on the reality of witches, Shaw’s Christian faith will lend a gravity to his storytelling.

As he put it to me in our interview, “I’m not trying to flog anything, I’m not trying to sell anything. I just gathered as many beautiful things as I could in a pile about the condition of living, and that is Liturgies of the Wild. That’s it.”

For those who are perfectly content only reading their Bible, Shaw is happy to leave them be. But for those who, like him, are “innately piratical” and are itching for something more, he hopes these stories can bring forth deep truths that can harmonize with Christian teaching. He calls this a “hinge” book, something that could appeal to a wary non-Christian and Christian alike. To both he says, “Come and see.”

Liturgies of the Wild is divided into 13 thematic chapters with titles such as, “On Death,” “On Passion,” and “On Evil.” Shaw has led an interesting life, and this book is bursting with the polished stories of his repertoire and his own life. For instance, after telling the story of “The Horse and the Firebird,” he casually mentions:

I once told this story with the great John Densmore of The Doors accompanying me on percussion. Later he told me he felt Jim Morrison let go entirely of the horse and jumped on the back of the firebird: Watching him on stage every night was like seeing a man in a microwave—he was going to get incinerated.

Shaw often gets grouped with Paul Kingsnorth—they’re both English with a deep love of nature—and some see Liturgies of the Wild as a sort of spiritual successor to Kingsnorth’s Against the Machine. But whereas Kingsnorth’s book is more analytical and pessimistic, Shaw’s is more intuitive and optimistic. He says a very few of us can walk out of The Machine entirely, so for most of us, we need to be “angels in The Machine.”

When I ask him whether stories can truly make a dent in such a distracted, overstimulated culture, he doesn’t hesitate for a moment. First off, he’s been telling these stories for 30 years, “in real time to people from all sorts of walks of life. That could be at-risk youth, could be politicians, it could be theater directors, it could be single mums, it could be recovering junkies.” He knows they work.

What’s more, he recently told the story of The Odyssey for five days straight in Crete, and despite “people’s apparent lack of concentration and the distraction of the screens, none of that really came into it. We just turned the screens off, and the good news is the recovery time of your sort of primordial mythic imagination is by no means as distant as you may think.”

When I ask Shaw how he decides what stories to tell and retell, he says to beware of stories that want to seduce you, “but if a story is trying to court you, trying to have a conversation with you, a real dialogue, such as The Odyssey, such as Beowulf, such as the Gospels, whatever it is, one way or another, those are the things to show fidelity to, to keep coming back to.” He says those stories call to us because they have something we need. They can heal us if we open ourselves to them.

In one sense, we are awash in stories today—turn on the news, turn on the TV, turn on your phone, there’s more there than you could ever watch or read. But in another sense, they are not stories at all. They may have a distinct beginning, but there is never clarity or closure, just an endless stream of information, updates, and alerts.

Unlike the infinite scroll online or the “Visual Muzak” Netflix is pumping out, Shaw’s stories are dense, potent, and concise. They often end so abruptly that he takes a few paragraphs afterwards to draw out themes and symbols that may be lost on the average reader. He holds your hand but never in a patronizing way. He brings you along on the journey as he tells stories most readers will have never heard before.

Shaw writes that, “There’s no one in the whole wide world that isn’t carrying a story…And God almighty you need to tell it, to rest in it, to find some peace with it.” That kind of knowledge only comes from spending time in silence, in nature, in solitude—the sort of thing that’s hard to come by nowadays.

But Martin Shaw’s life bears witness to the power of story to change people’s lives, and for those who wish to join him, Liturgies of the Wild offers a way in. Frankly, it’s hard to look at him and not think, “I’d like a little more of that in my life.”

I discovered Martin on Justin Brierley’s Re-enchanting podcast, what a wonderful and eloquent man!

Handsome prose